Urban Mining - The City as a Source of Raw Materials

Built structures are everywhere, they are a mark of civilization, defining spaces of human settlement and activity for the last couple thousand years. But also the built environment is a gigantic agglomeration of material resources. Buildings, infrastructure all man-made surroundings have been produced to function within their current purpose. This purpose shifts over time, a building that was needed two decades ago becomes obsolete now, as requirements change.

In the last few hundred years the usual reaction to these changes was the demolition and rebuilding of structures, making this a very short-sighted, unsustainable process as only the current use of the building was in the focus. In recent years a more transitory and less static approach to the building economy has been re-discovered, which facilitates a change of use of a building and an exchange of material resources within the built environment. It is nowadays named Urban Mining.

It is a response to the growing demand for raw materials within a world with limited natural reserves. Alternatively, Urban Mining states that these resources can be found within our most immediate surroundings: It regards the city as a field of material resources for further development.

It is by no means a discovery, however, it has been undervalued within the present 'take-make-waste' linear system. The reuse of materials was carried throughout a great part of the architectural history, and can even be dated back to antiquity.

The word Spolia, derived from Latin "spolium" - meaning spoils, plunder, loot - refers to the reuse of architectural fragments in new constructions. It was a rather common practice and can be virtually found on every ancient site across Southern Europe. Materials were reused for practical purposes - for instance, exerting pre-cut stone slabs from ruins to build a new wall - and for aesthetic and symbolic reasons - whereas entire ornamented pieces would be applied to new buildings, even conveying different meanings to them. Thereby in this process, every new structure carries within it both cultural and material elements from the past.

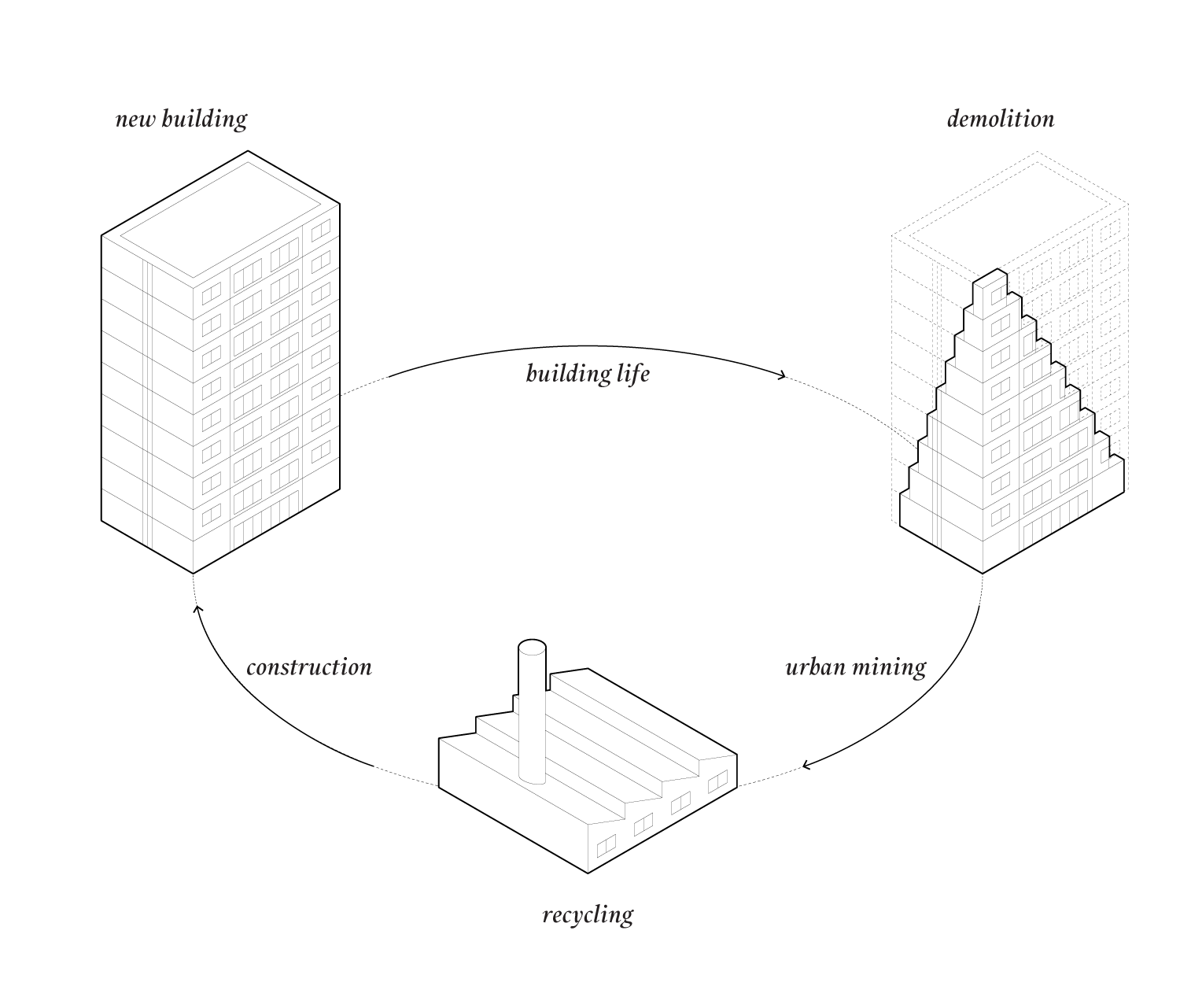

Urban Mining could then be the present-day interpretation of the concept of Spolia. Its principle is that all building materials are only temporarily used within one structure and can be set free to be used for new structures again. For example, the steel beams used for the structural support of one building will form the basis of another building. One distinction to Spolia, though, is that it focuses not solely on individual architectural fragments but aims to create an efficient cycle of repurposing existing material stocks within the urban space. Urban Mining emphasizes a free exchange of materials to create a system of reuse and recycling.

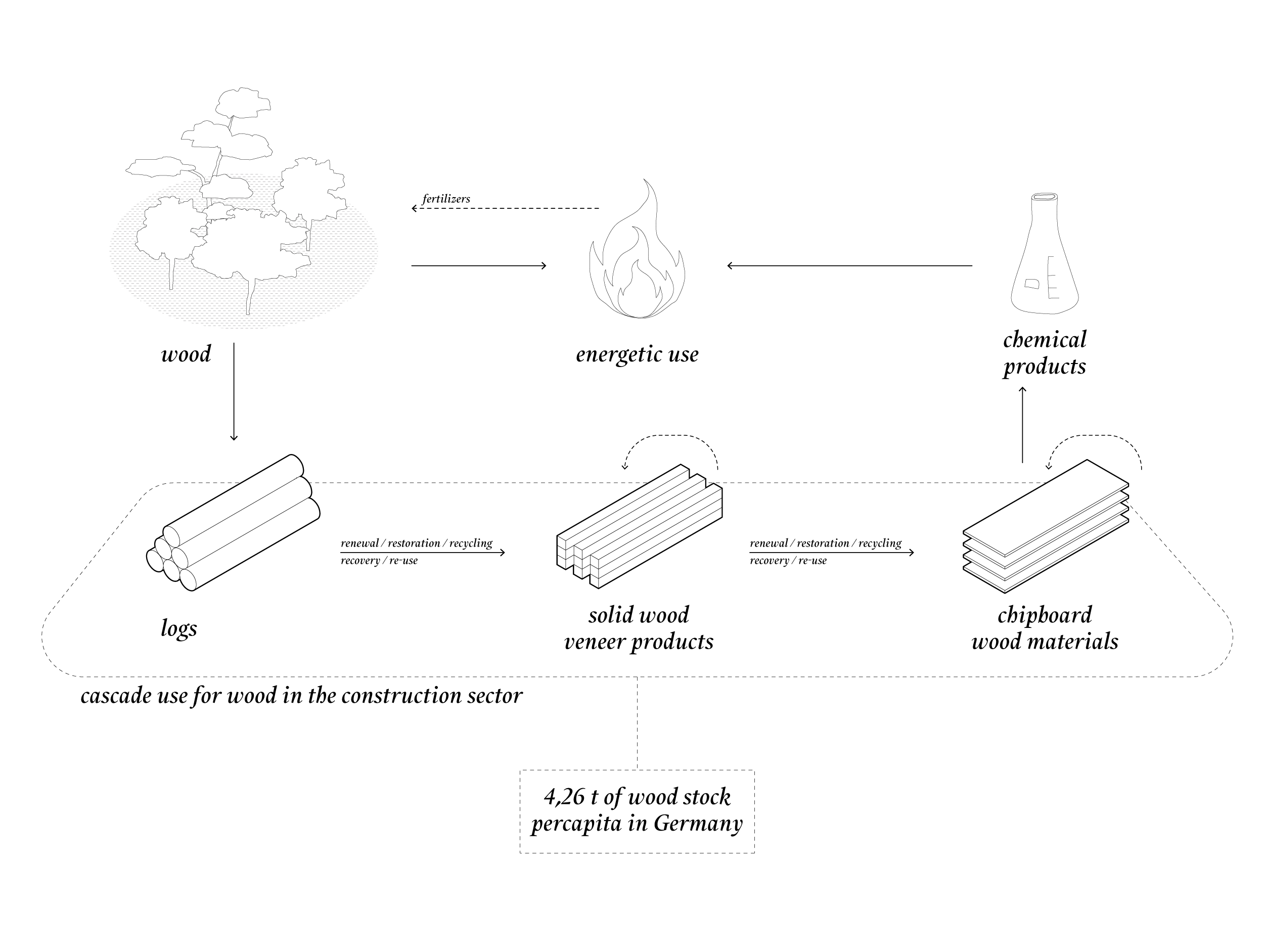

This strategy can be particularly beneficial when considering that approximately 1,500 tonnes of material can be reclaimed from the demolition of a ten-unit building. Amongst them, one can retrieve 70 tonnes of metals and 30 tonnes of plastics, bitumen, and wood. The intelligent management and monitoring of the availability and quantity of the raw materials are fundamental for their further reuse. It is a significant challenge to determine the total amount of these goods, but it is estimated that the construction sector holds the largest share of this stock. In Germany, the known material stock percapita consists of nearly 4.26t of wood and 317.27t of mineral materials.

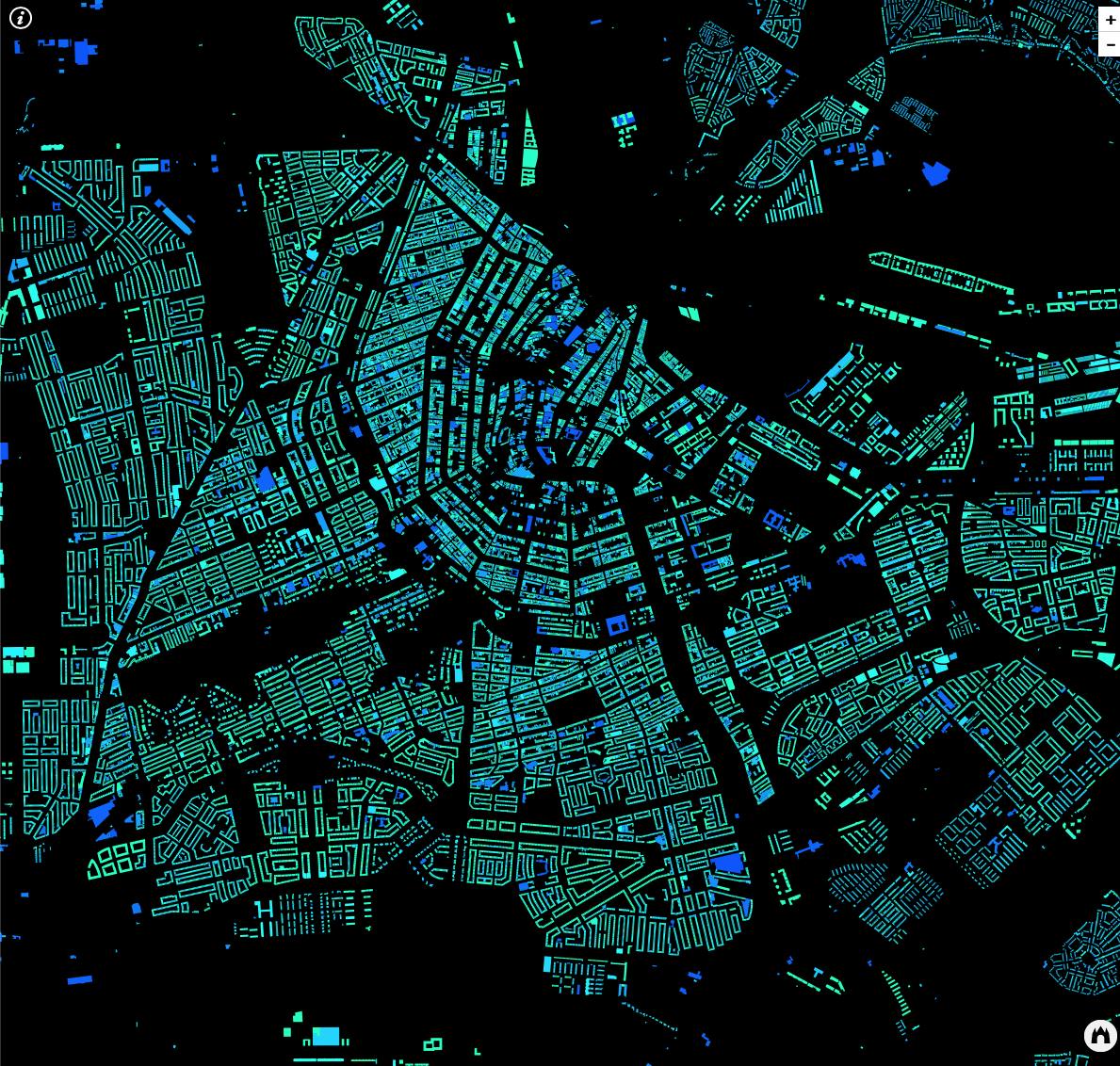

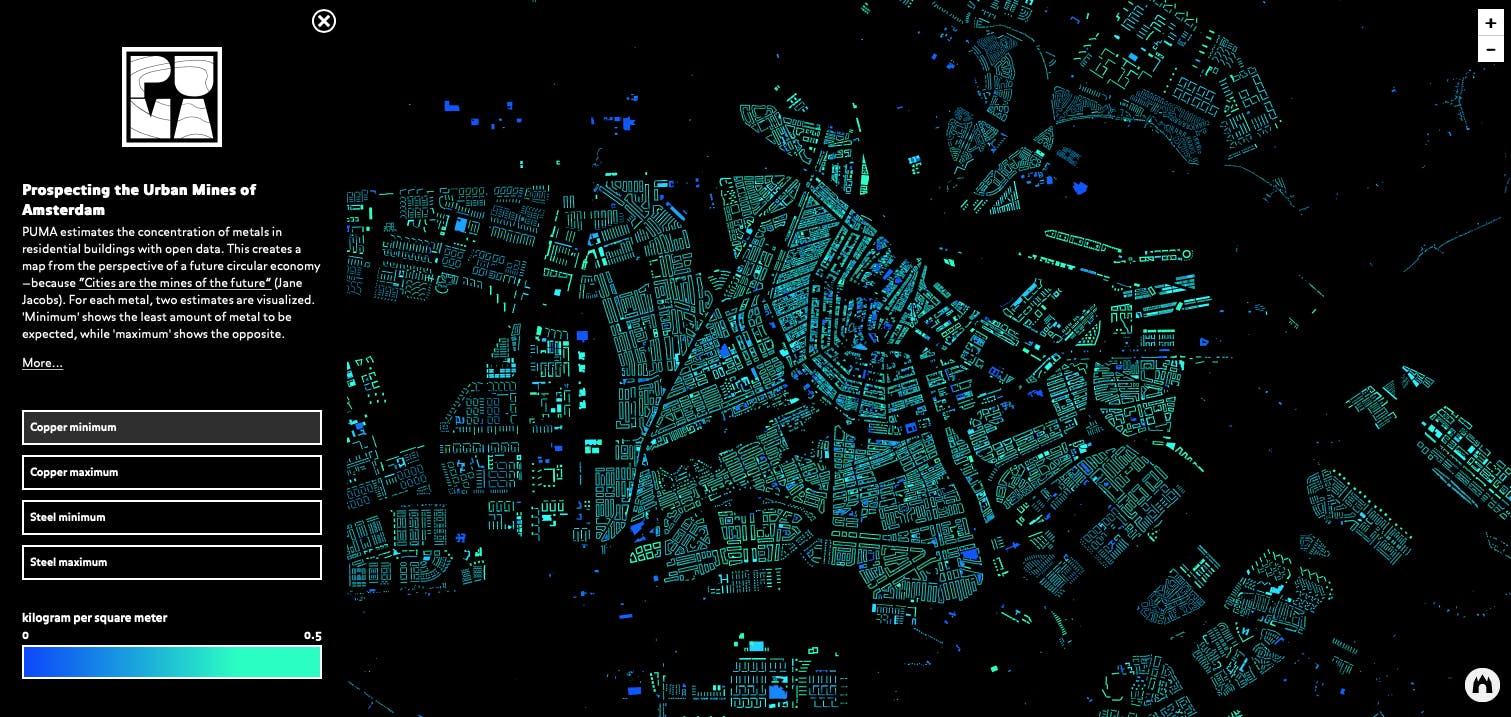

A project led by Leiden University, Delft University, Waag Society, and Metabolic Institute focuses on estimating the number of available resources in Amsterdam’s urban mine. This study is named PUMA** (Prospecting the Urban Mines of Amsterdam) and one of its results is an interactive map where one can visualize the maximum and minimum estimates for different materials in the city. The researchers acknowledge that most of these stocks are in use and that it may take several years before they can be repurposed. However, it operates similarly to a traditional mine, which also needs decades to begin its operations. The next step is outlining a plan to exploit the resources. It is a significant first step in creating an urban mining system, whereas to date none exists.

Additionally to the control of available stocks, the cascade use of materials is also particularly relevant. It means that elements can be reused multiple times for different purposes. In the case of wood, solid pieces can ben reused as such and then be recycled into chipboard than can be further recycled, before entering a chemical digestion stage and finally energy recovery, when its products can be further used as fertilizer additives.

Traditionally a vast percentage of former building material, mostly mineral components like concrete and stone have been recycled, but with significant loss of quality in the process of its reuse. Mineral elements usually would be ground and used as low grade filling material in foundations and landscaping. Also, the process of producing and demolishing mineral structures increases global carbon emissions significantly.

Urban mining, by contrast, intends to reuse the existing building material and to retain its quality and value at the same time. To put this into practice, buildings need to be designed in a way that allows for their easy disassembly as it is the only way, the material can be extracted again without it being damaged or their quality being reduced drastically. Thus, the city becomes a material bank that can be accessed at any time to build new structures.

*see: 1) https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/479/publikationen/uba_urbanmining_en_2019.pdf

**see: 2) http://code.waag.org/puma

Back